What If Magneto Is Right?

“Never again” doesn’t mean again and again and again

It’s been a minute since I last posted a little more than two weeks ago. Following the successful conclusion of the Omega Reign kickstarter—and thanks once again to everyone for supporting it!—I took a little time off to recharge. Thanks for being patient with me. Onward!

One of the reasons why I love Shooter-era Marvel comics so much is for how its writers and artists made a ton of great superhero comics by questioning everything that had come before them. And I’m not talking about simple retcons; I’m talking about wholesale re-contextualizations of characters, stories, and themes in ways that made everything deeper, richer, and more meaningful than they had been before.

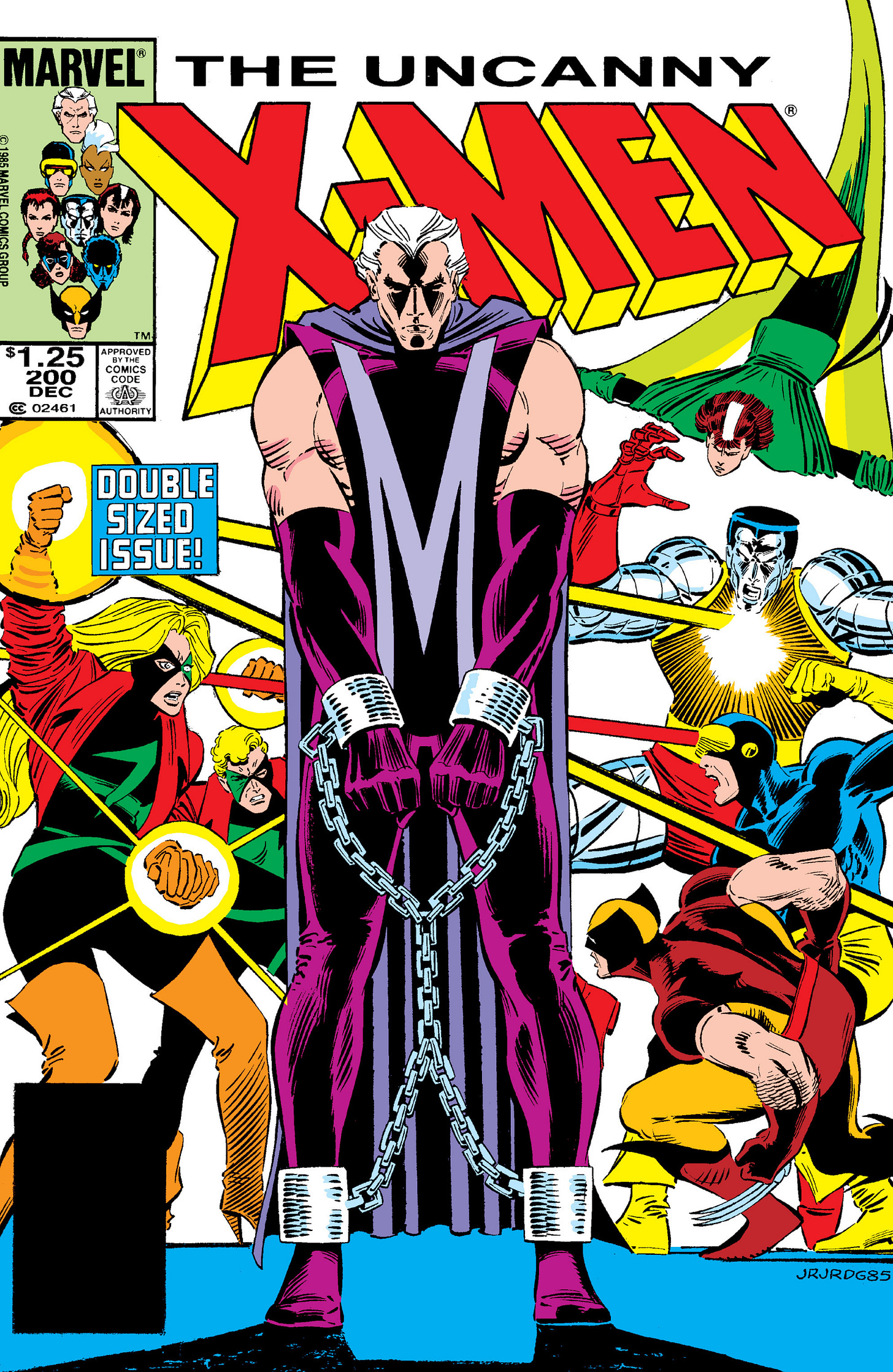

Perhaps the example of this that affected me the most was the rehabilitation of the X-Men’s arch-nemesis Magneto from power-mad megalomaniac to sympathetic antihero who took over Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters by the end of Uncanny X-Men #200. It was a remarkable and believable transformation thanks to the writing of Chris Claremont, who did even more for Magneto what what John Byrne did for Doctor Doom.

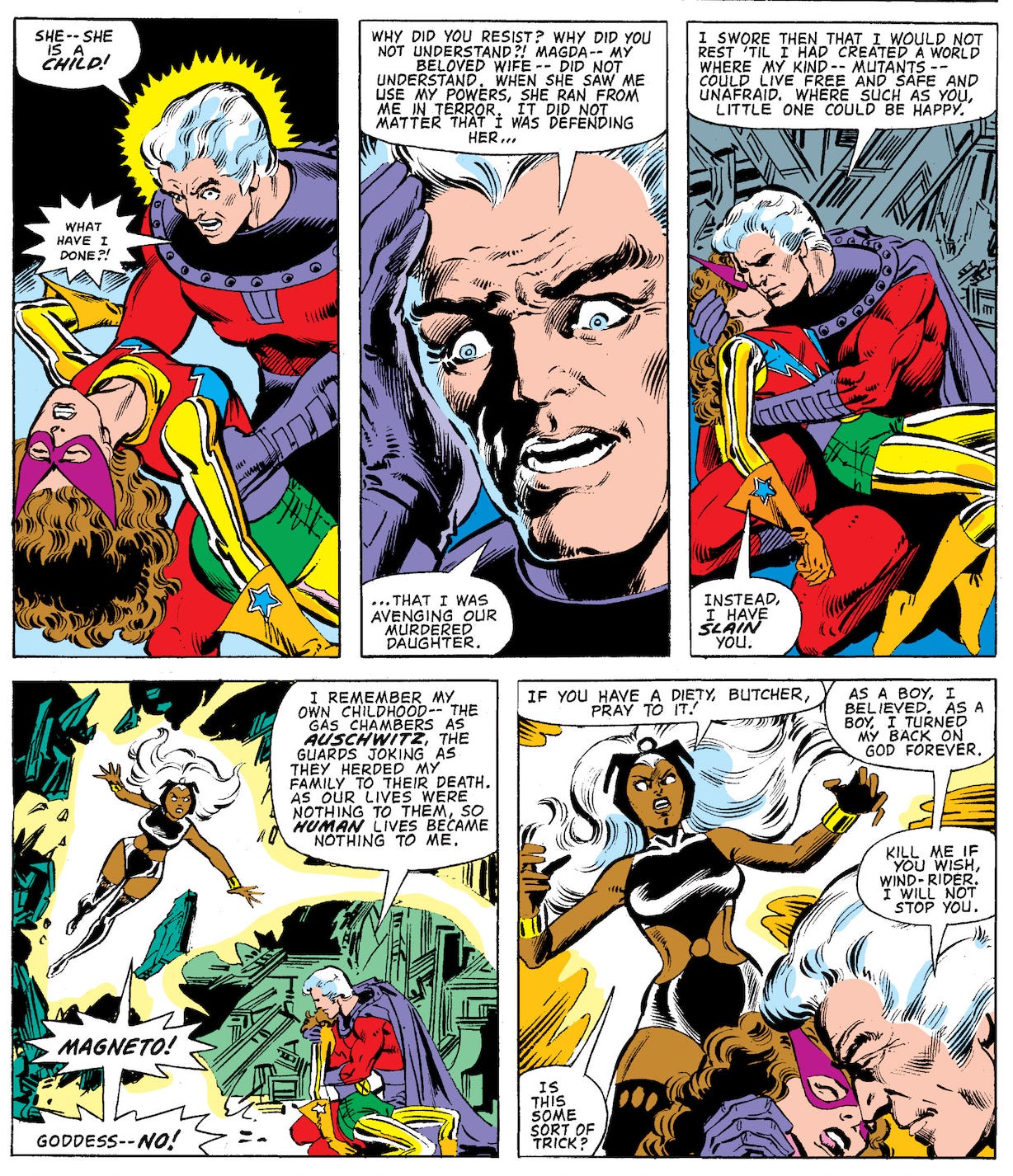

To fully appreciate this, we must first go back to Uncanny X-Men #150, in which the team confronts Magneto over his latest ultimatum: every world leader must dismantle all nuclear weapons and submit to mutant rule (with Magneto at the top, natch) or face destruction. It’s the kind of grand doomsday plot Magneto specializes in, but this time, he delivers it with enough sense to make us wonder if maybe somebody, somewhere ought to hear the guy out. He’s not wrong about the anti-mutant hatred around the world, or about how the money that goes into nuclear arms would do more good feeding and clothing people. For a guy who founded an outfit called the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, Magneto suddenly seems a lot less…well, evil.

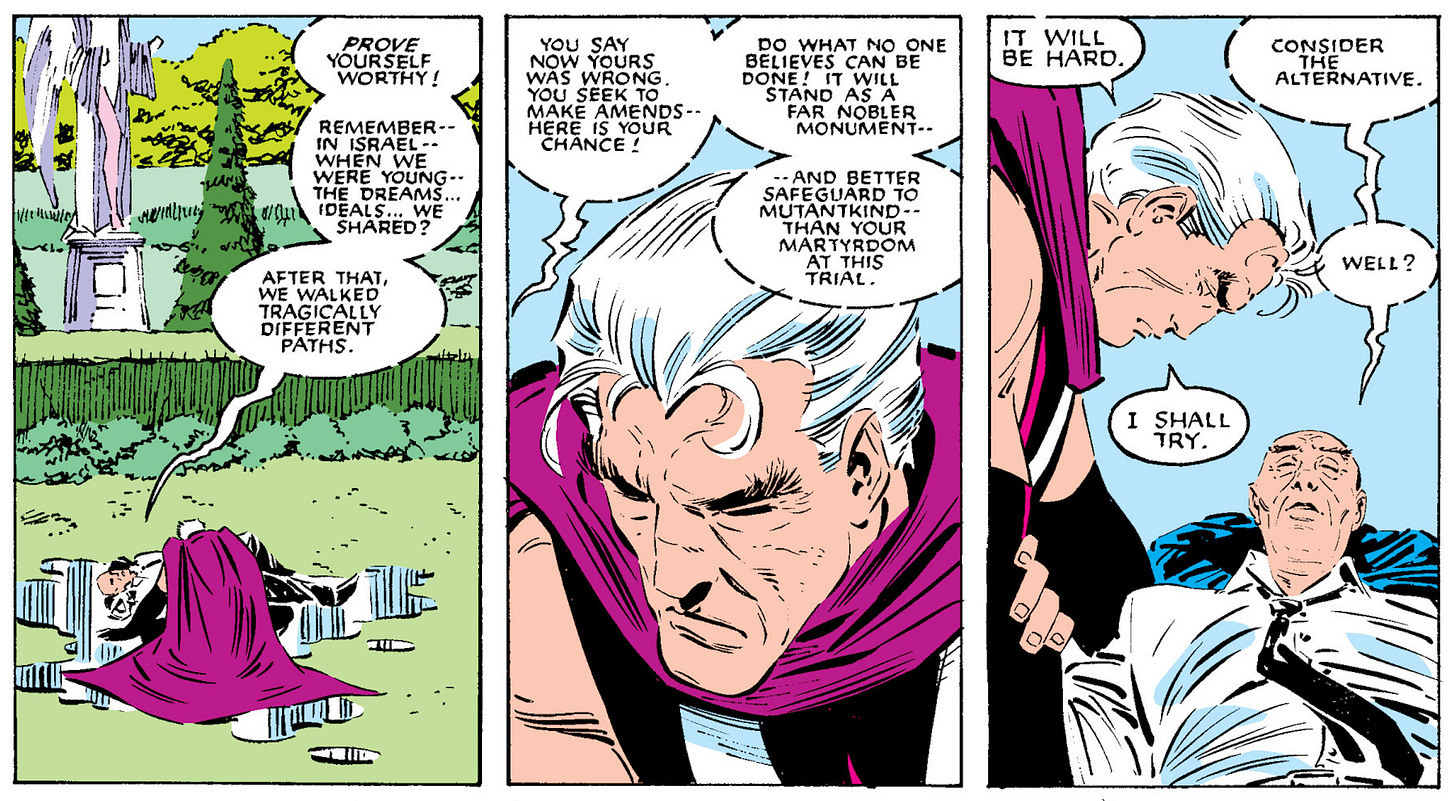

The X-Men began as Stan Lee’s comment on the civil rights movement, and the competing worldviews of Professor Xavier and Magneto lend themselves to comparing Martin Luther King, Jr. to Malcom X in terms of how to best protect an oppressed people. Claremont took it a big step further. In Magneto, he saw the arc of Manachem Begin, who went from terrorist to Prime Minister of Israel to co-recipient of the 1978 Nobel Peace Prize for his role in the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel. Claremont figured, if Begin could make such a journey, then perhaps the Master of Magnetism could, too.

Thus, in #150, we have this awesome scene where Magneto injures Kitty Pryde, and upon realizing she is just a young girl not that different from a daughter he lost, he immediately breaks down and repents. He reveals that he is a Holocaust survivor, whose homo superior fanaticism stems from the genocide he experienced. For Magneto, “never again” paves the way to all kinds of necessary evil. Once he realizes just how wrong he is, he stops fighting and submits to the X-Men. As far as supervillain collapses go, it’s one of the more poignant and context-altering ones. Forevermore, we can’t condemn Magneto entirely without also condemning ourselves.

From here, we don’t see much more of Magneto—he guest stars in the Secret Wars as a kind of neutral, showing us just how much he has stepped toward the light, if not out of the shadows. By Uncanny X-Men #199, he is on friendly enough terms with the X-Men that he accompanies Kitty Pryde to a Holocaust survivors event, where he is attacked by the very Brotherhood he once led, (now working for the U.S. government, no less). Magneto and the X-Men win the brawl, but Magneto surrenders to custody to answer for his history of crimes. If he can’t reckon with his own past, he can’t expect anybody else to reckon with their own.

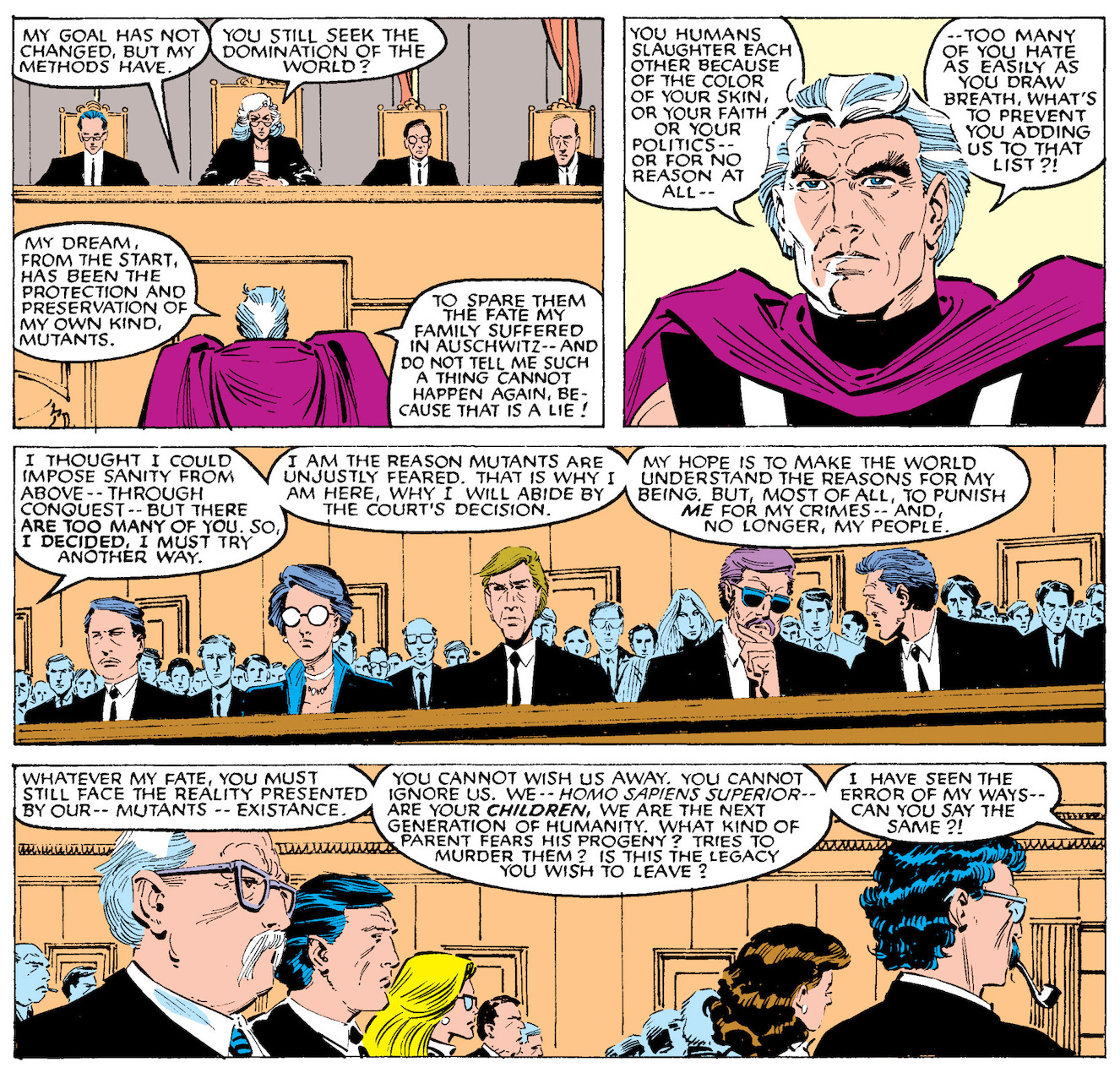

His defense counsel is Gabrielle Haller, Israel’s ambassador to the UN, and someone Magneto and Xavier once rescued from the clutches of the Nazi villain Baron von Strucker years before, in Israel. (How’s that for context?) Prosecuting Magneto is Sir James Jasper, the attorney general for the United Kingdom, whose own willingness to bash a mutant’s head with a rock makes one wonder what he thinks about the Irish.

The trial is politically charged as it gets; everyone who has something to say about it has blood on their hands they’d rather not admit to. And that’s before Strucker’s goose-stepping kids attack the proceedings, eager to kill Magneto, Xavier, and Haller to avenge their father. Because what this volatile situation really needs is actual Nazis storming the place.

It all ends with Magneto acquitted, Xavier on death’s door, and Magneto agreeing to pick up after his best frenemy. High drama? You bet.

We don’t like to acknowledge how superhero comics can be political—overtly or otherwise—because then we have to acknowledge some really awful truths about a world for which we are responsible. But the reality is this: within Magneto’s rehabilitation is the notion that no people deserves extermination, and that good and evil aren’t about where you were born, who your parents are, or things that happened when you weren’t even alive yet.

When Uncanny X-Men #200 came out, it caused no great controversy except among fans who preferred Magneto as a simple bad guy. Had this issue—or The X-Men #1, for that matter—come out today, Magneto probably wouldn’t have sunk a Soviet submarine. He would have intervened in Gaza to stop an Israeli war machine perpetuating a genocide it was built to prevent, in a potent statement about great power and great responsibility.

After all, it doesn’t take superpowers to know that real heroes don’t take part in massacres, no matter what their reason. They prevent them. They stop them. They say “never again,” and mean it. Not just for themselves, but for everyone. Just ask Magneto. He’ll tell you. The guy’s a lot of things, but a liar’s not one of them.