First-Time Jitters

Being a superhero means working at it

It’s hard to imagine a world in which Batman doesn’t sell out each and every issue. And yet, the title has struggled over the years. In the 80s, like the rest of the DC universe, Batman wasn’t in a great place, saleswise. In 1986, Frank Miller’s blockbuster The Dark Knight Returns kicked off a Batman mania in wider pop culture, but strangely not in the core title bearing the Caped Crusader’s name. Batman’s sales were lousy in the mid-80s, and they remained so even when The Dark Knight Returns was racking up huge numbers.

Thankfully for DC, when they contracted Miller for the Dark Knight Returns, they also contracted him for an origin story. Miller partnered with his Daredevil collaborator David Mazzuchelli to produce Batman: Year One. And to boost Batman’s flagging sales, they ran it not as a graphic novel, but as a four-issue story arc from Batman #404-407.

It was an unusual move, especially when you consider the tonal whiplash Batman: Year One must have inflicted upon monthly subscribers. But did it get me to buy those issues? Absolutely. And by the powers, am I glad it did.

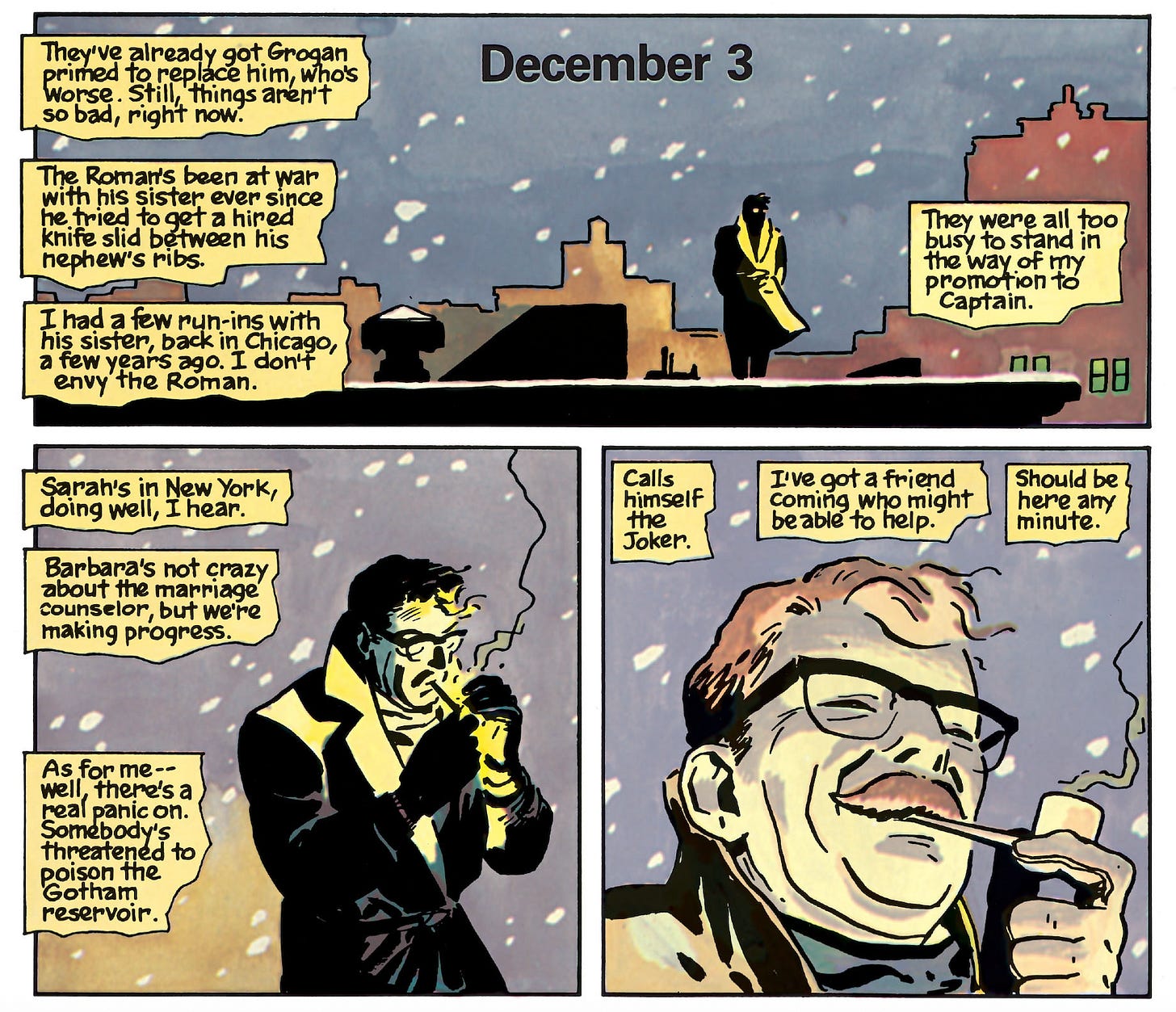

Batman: Year One is easily one of my favorite Batman stories, a gritty, noir take on Batman’s decision to fight crime in costume, and how it all goes wrong before he finally gets into gear. It’s something Miller worried about writing, since it would require him to tread in canonical territory, unlike The Dark Knight Returns. But by developing unexplored bits of Batman’s early history, we get a tale that enriches Batman’s official history and impacts how we imagine superheroes in general.

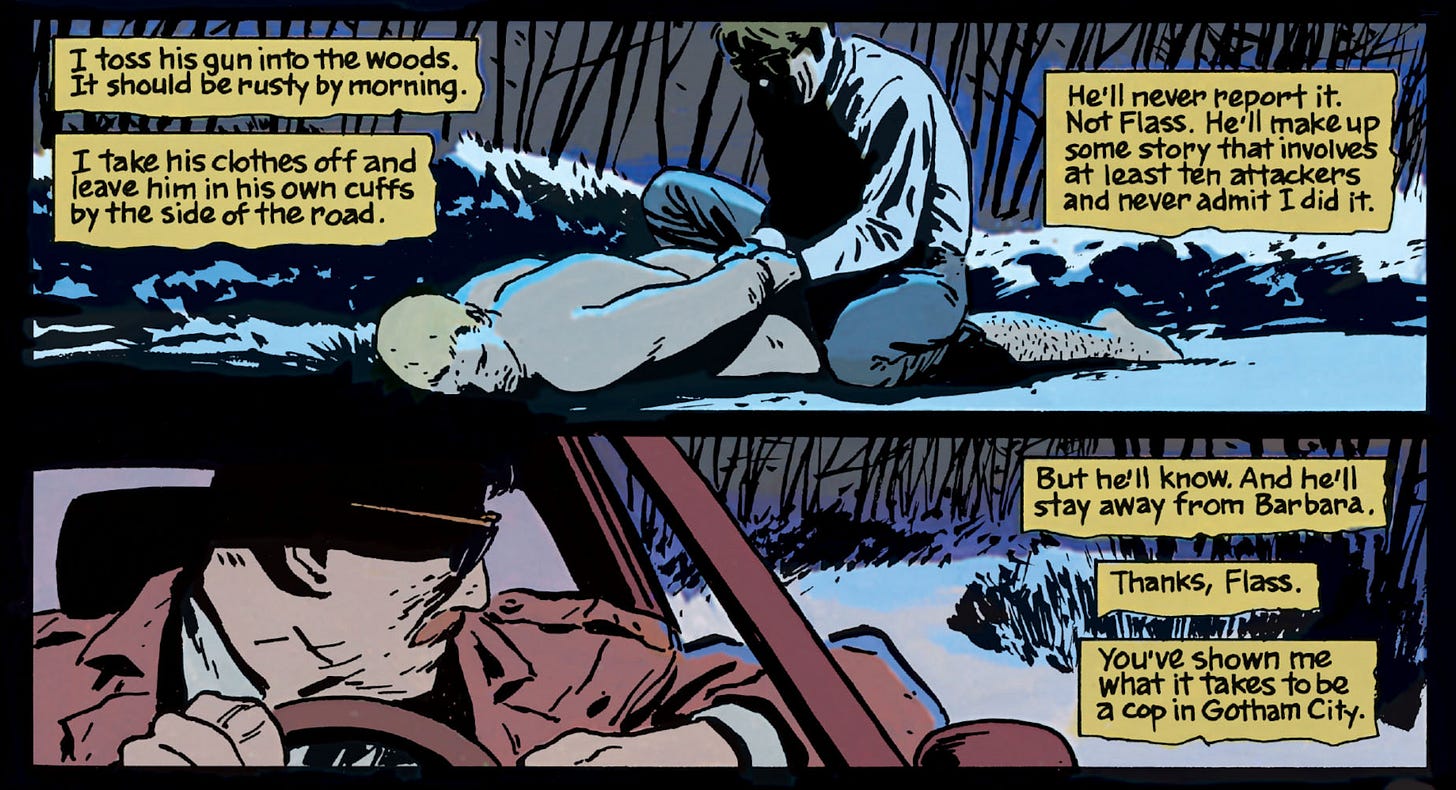

Part of the magic comes from focusing equally on the origin of Police Commissioner Jim Gordon, a lieutenant with a checkered past and Gotham City transplant. Through his eyes we see not just how rotten Gotham City has become, but that its police are the worst of its criminals, interested in protecting and serving only their own corruption. As blunt as he is honest, Gordon swiftly makes mortal enemies of his colleagues, who try unsuccessfully to bludgeon him into submission. When we see Gordon deliver some physical justice of his own, we begin to understand why it makes sense that he will find a kindred spirit in a certain costumed vigilante.

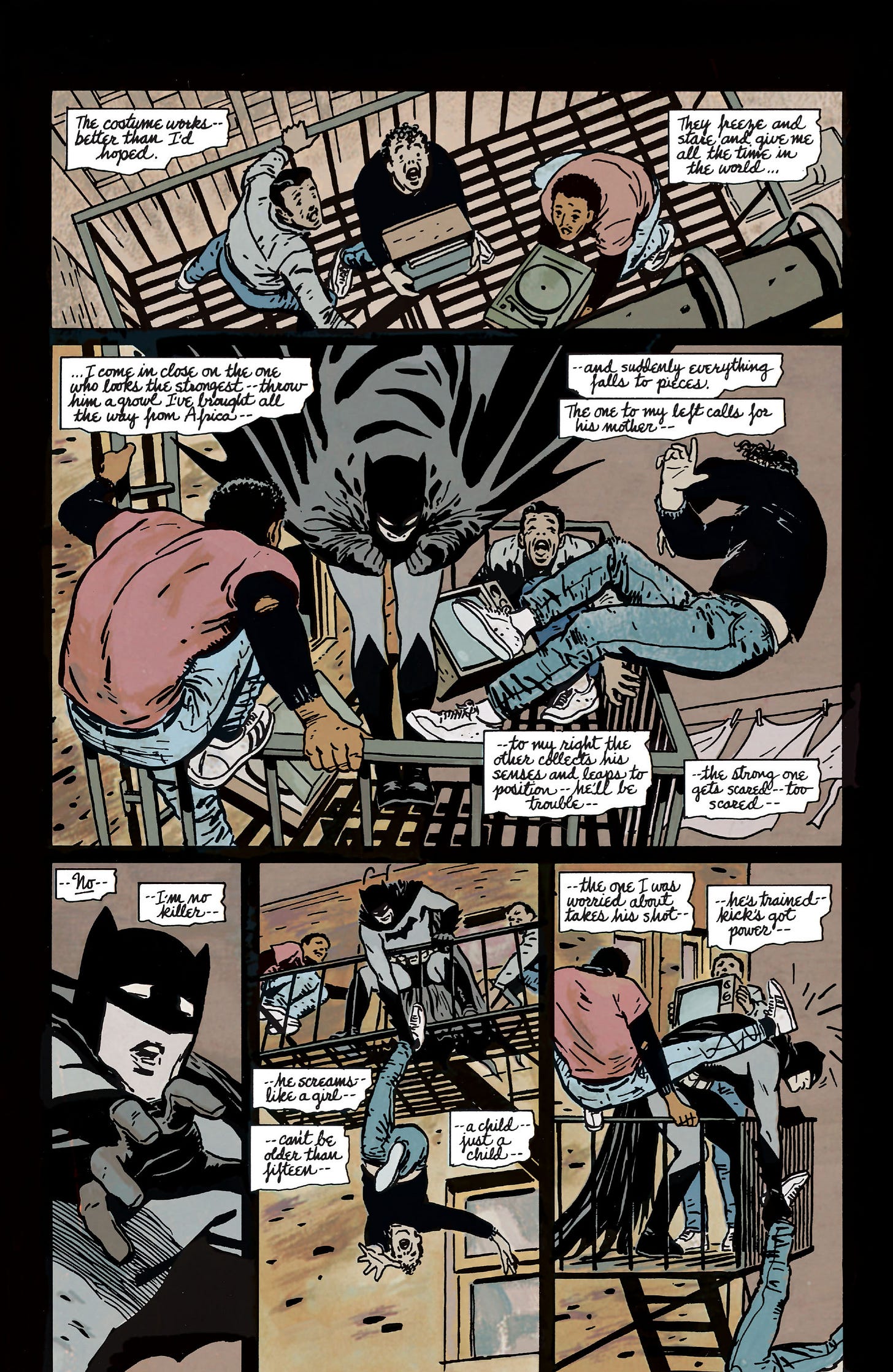

Bruce Wayne doesn’t know it yet, but he will need Gordon just as much as Gordon needs him. Crimefighting doesn’t suffer novices lightly, and Batman’s first efforts to bring justice to Gotham’s criminal ecosystem are a disaster. He picks the wrong fights. He doesn’t understand the people he’s trying to save. And doesn’t yet understand that the city needs justice, not vengeance.

In his first scene in costume, the ensuing fracas veers so wildly off-plan that it’s a miracle Batmen even survives it. For a tense three pages, Batman surprises some burglars on a fire escape, but he almost kills one by accident and opens himself up to a real beating from the others. If this Batman thing is going to work, he’s going to need to develop his craft in ways he never imagined, and for which there is no instruction manual.

To see Batman like this in his journeyman days makes us wonder what kind of first-time jitters any other superhero must have had during their first costumed outing. After all, nobody gets anything right the first time. Not even Batman.

It’s worth nothing that Bruce Wayne first tries fighting crime merely as a civilian in disguise and ends up brawling with the very street prostitutes he tried to save. Wounded and humiliated, he realizes that Gotham doesn’t just need someone to pummel human predators. The city is too far gone for that. That’s why he must adopt his Batman persona and elevate himself to something mythic and primordial to strike fear into the heart of evil itself.

Likewise, it’s worth nothing that Jim Gordon hates his job but refuses to quit out of the kind of stubbornness (and occasionally poor judgement) that probably got him shitcanned to Gotham in the first place. He realizes that simply being a good cop in a rotten department is not enough. The city is too far gone for that, too. And thus, he decides to ally with a certain costumed weirdo in a city that appears to be filling up with them. Gordon’s got sense enough to know when it takes a thief to catch a thief, and Batman’s got sense enough to know that its not a weakness to depend on people you trust.

This sublime telling of a time when the World’s Greatest Detective did not yet deserve such a title stands in stark contrast to every other Batman story that preceded it. Miller sensed that superheroes are most interesting when they’re at their least competent, and he explored that right when superhero comics really began to deconstruct themselves. And it wasn’t to dunk on Batman or to dismiss the notion of superheroes but to explore the idea that making a real difference in the world requires great physical, mental, and moral toil. Batman might not have powers, but he reminds us that they’re that just a shortcut. Real heroism comes from putting in the work. And that holds true no matter what your chosen profession might be.