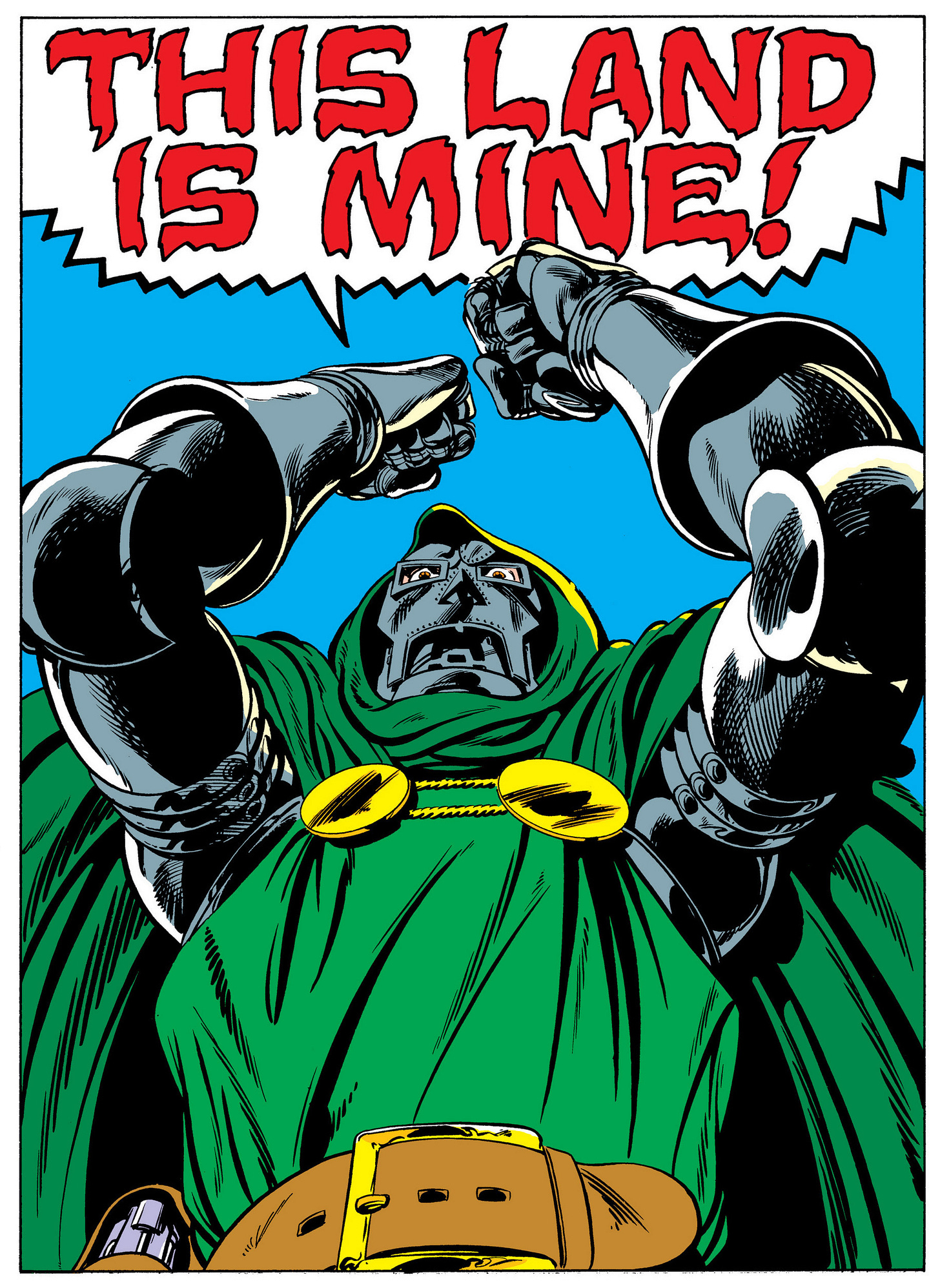

Of Marvel’s original stable of villains, are there any better than Doctor Doom? Bah, you fool! That was a trick question! Doom needs no answer! He’s one of those S-tier bad guys whose intellect and ambition is matched only by his ego and cruelty. As ruthless and manipulative as he is, we appreciate his ingenuity, and the aberrant principles that compel him. Even if we hate evil, we love a bad guy who lives by their own rules. Doom may try to kill you or take over the world, but he won’t lie to you. And he won’t stoop to pettiness, either. Even at his most bombastic, he never veers into self-ridicule. Such is his dark charisma that we can fear Doom, we can dread him, but we can never, ever laugh at him. Of all of Marvel’s villains, he commands the most respect. Yes, even more than Galactus. Devouring a planet is far easier than ruling one.

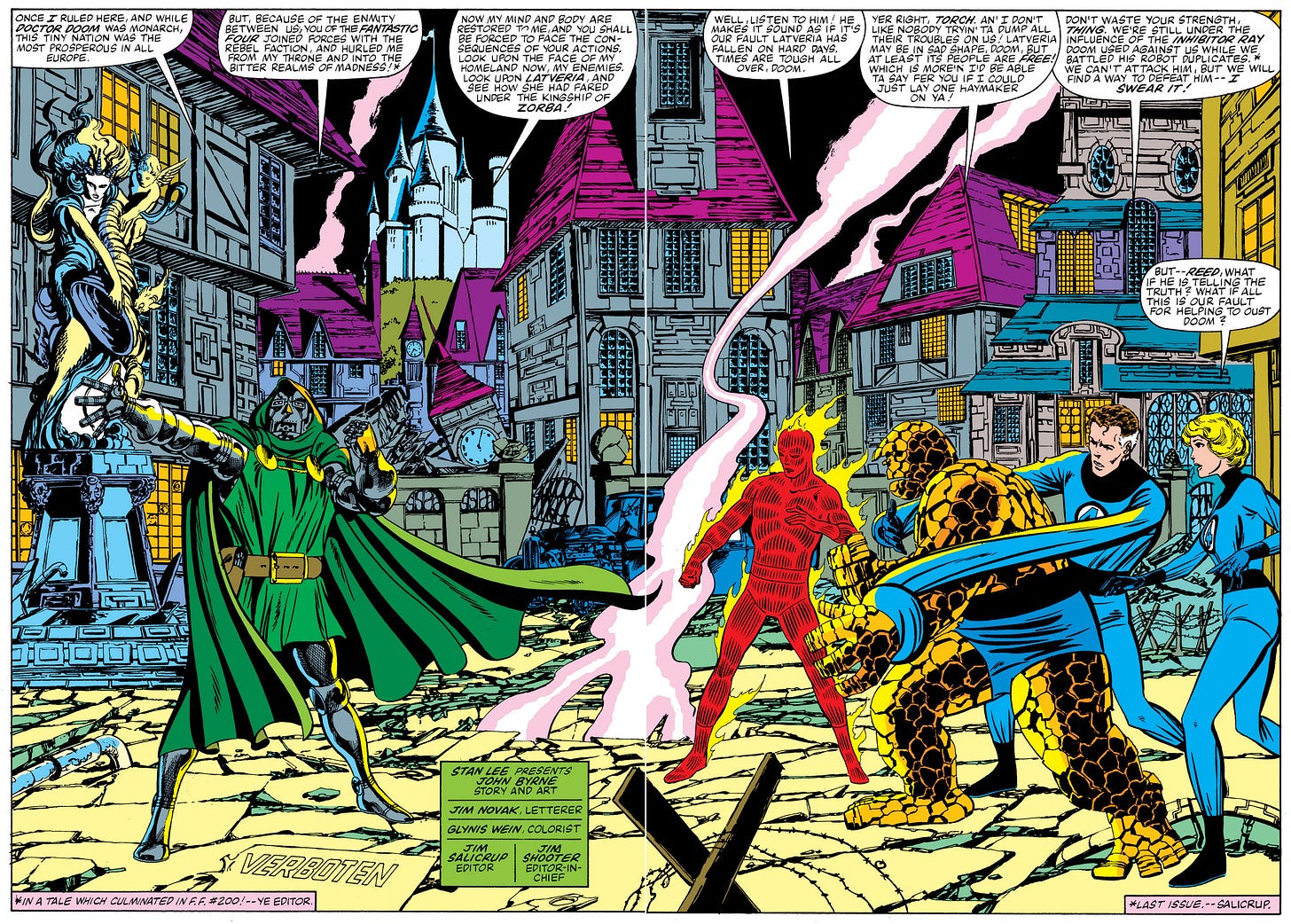

In #236, John Byrne reintroduces Doom in grand fashion after Latveria fell to rebels and Doom himself rendered catatonic in #200. Issue #236 opens with the FF living mundane, alternate lives that have been engineered by Doom himself with the help of the Puppet Master. Together, the two have built this miniature town called Liddleville, populated by minuscule robot people. They capture the FF, transfer their minds into tiny robot versions of themselves, and silently gloat over their powerlessness. Eventually the FF figure out what’s going on and manage to free themselves while the Puppet Master turns on Doom and traps his mind in Liddleville We don’t see Doom again until nearly a year later, when he manages to free himself, abducts the FF once more, and transports them to Latveria so they can help him take his old country back. The guy who overthrew Doom is even more of a cruel dictator than Doom ever was and has run Latveria into the ground. Turns out, the only thing Doom can’t stand more than the Fantastic Four is to see his home country under new management.

The wild adventure that follows restores Doom to power in a new version of himself. From this point on, Byrne (and every other writer) really leans into the notion that Doom is a proper head of state, with all of the rights and privileges that come along with it. He still plots to destroy the FF, but he does it through minions and cat’s paws rather than himself; the weird fistfight between Reed Richards and Doom that ended issue #200 will never happen again. Such things are beneath Doom. And if there is one thing Byrne will not let us forget, it’s that everything is beneath Doom.

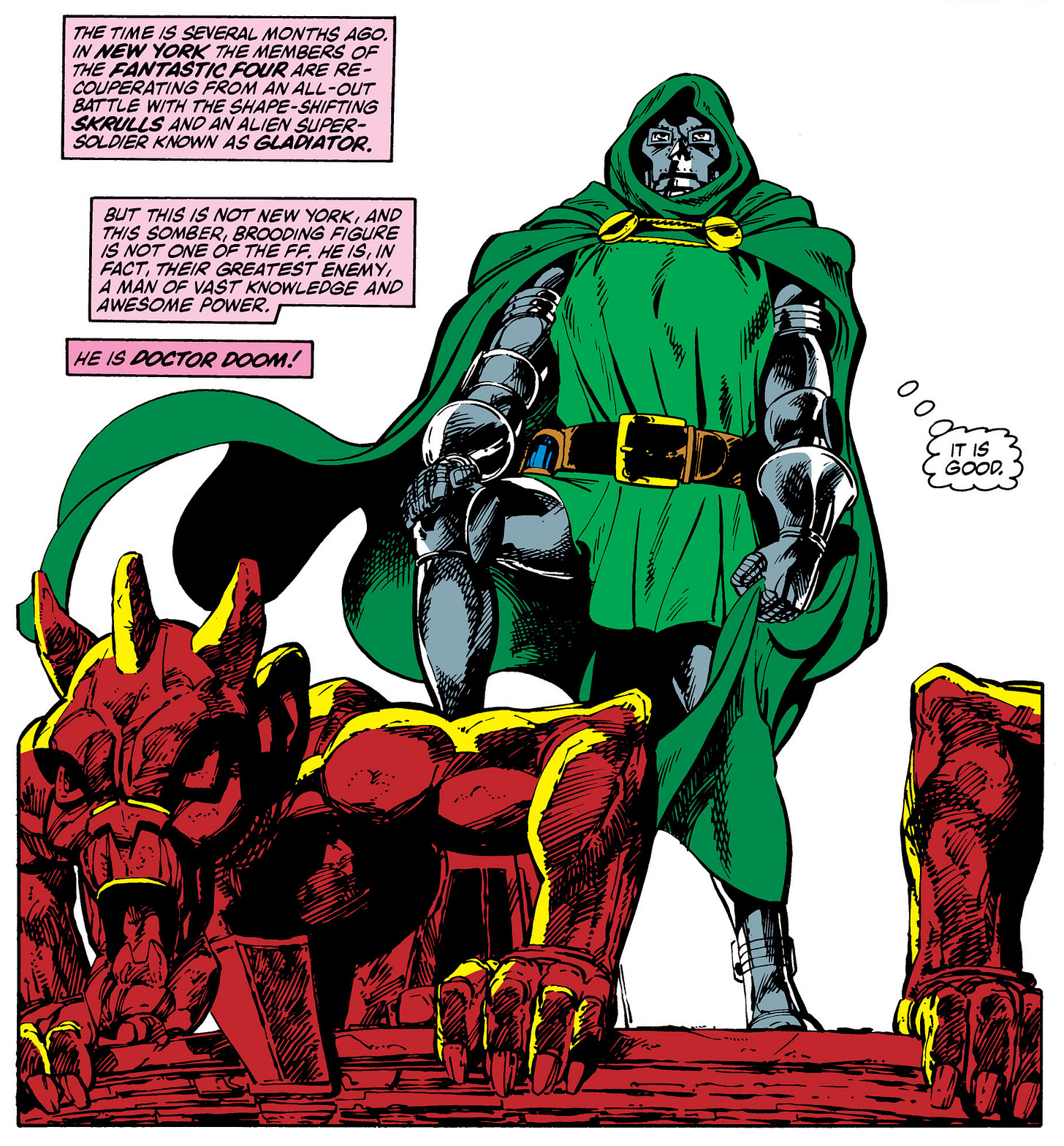

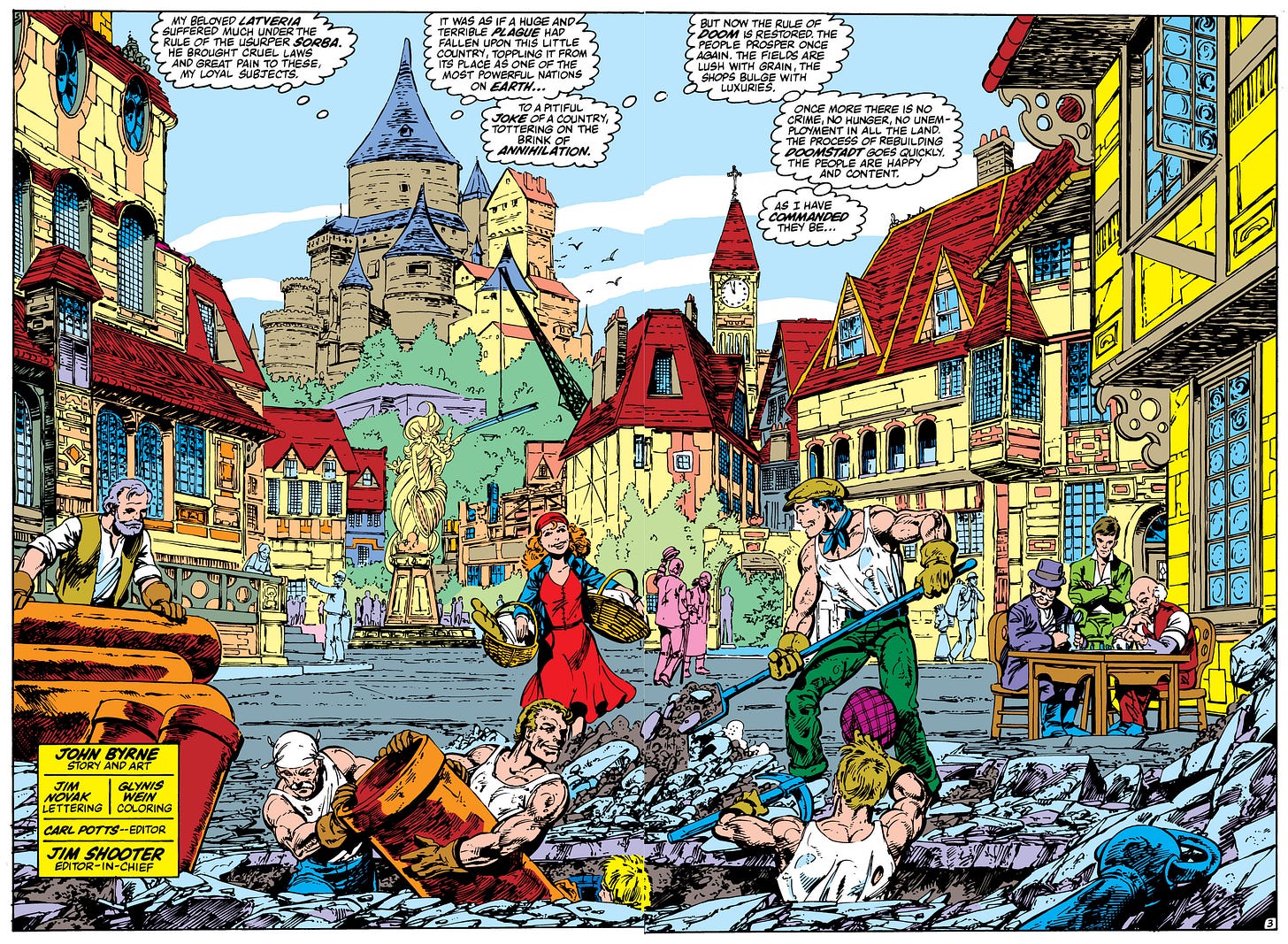

Where this comes to fruition is in #258, when we get a really fun interlude that follows Doom for a day while he tends to his business of running Latveria. The people are glad he is back. Life has returned to what passes for normal when your leader is an armor-clad despot. Things are actually prospering. And for at least one glorious splash page, is almost seems like Doom is content.

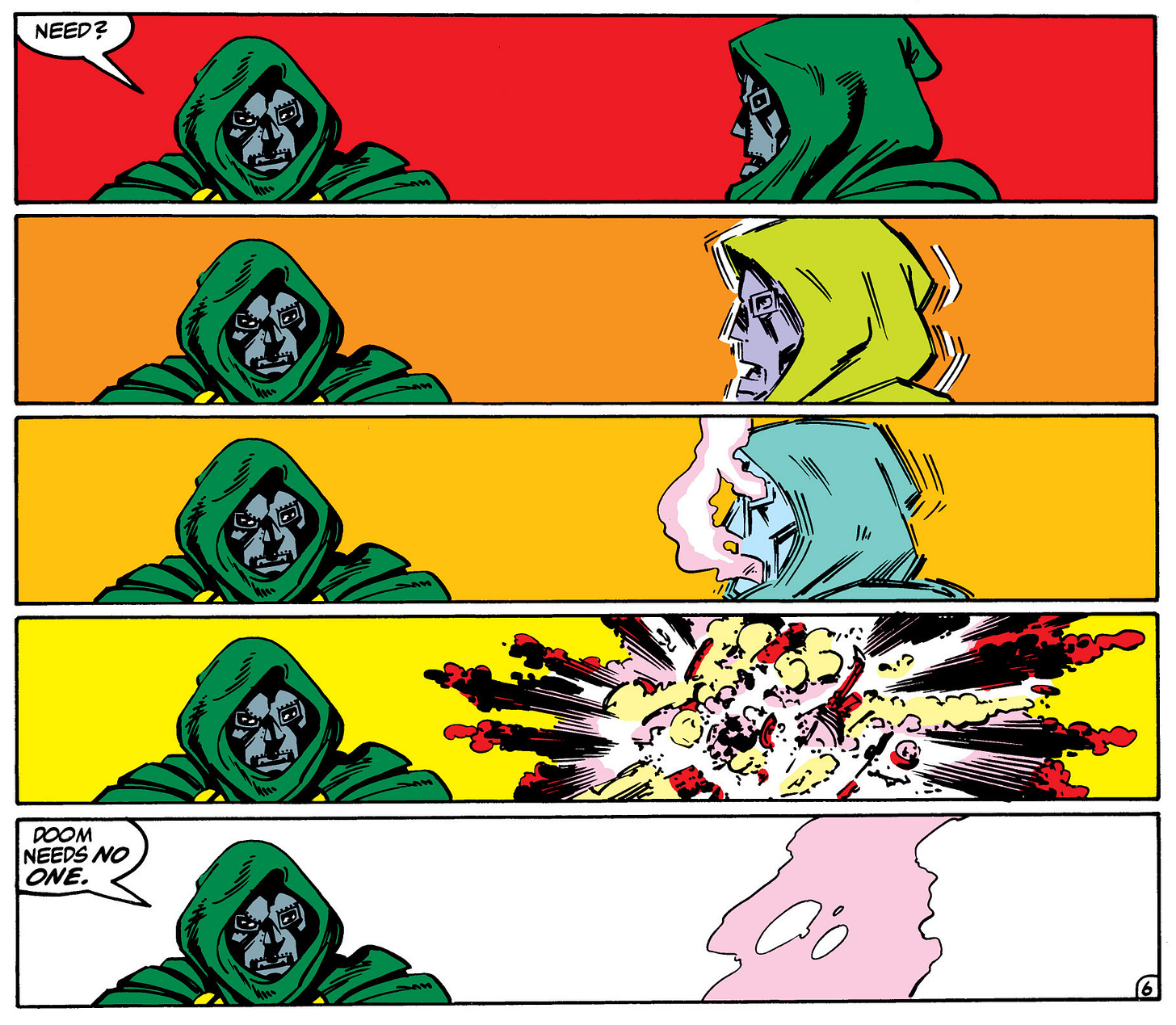

Except that he is not. An egomaniac like Doom never can be. What drives them is a gaping chasm where their heart ought to be and could never be filled if the whole universe was poured into it. He knows that he needed the FF’s help to regain Latveria, and he hates himself for it. Doom pathologically insists he needs no one’s help, even though he knows he couldn’t have regained Latveria without the FF’s help. He knows that no tyrant dies of old age, so he projects his power for the dumbest reasons. When a Doombot reveals that it decided against killing the villain Arcade because Doom might need Arcade as a useful pawn one day, Doom glares at the robot so hard it self-destructs. His resentment and self-loathing is nearly a superpower itself.

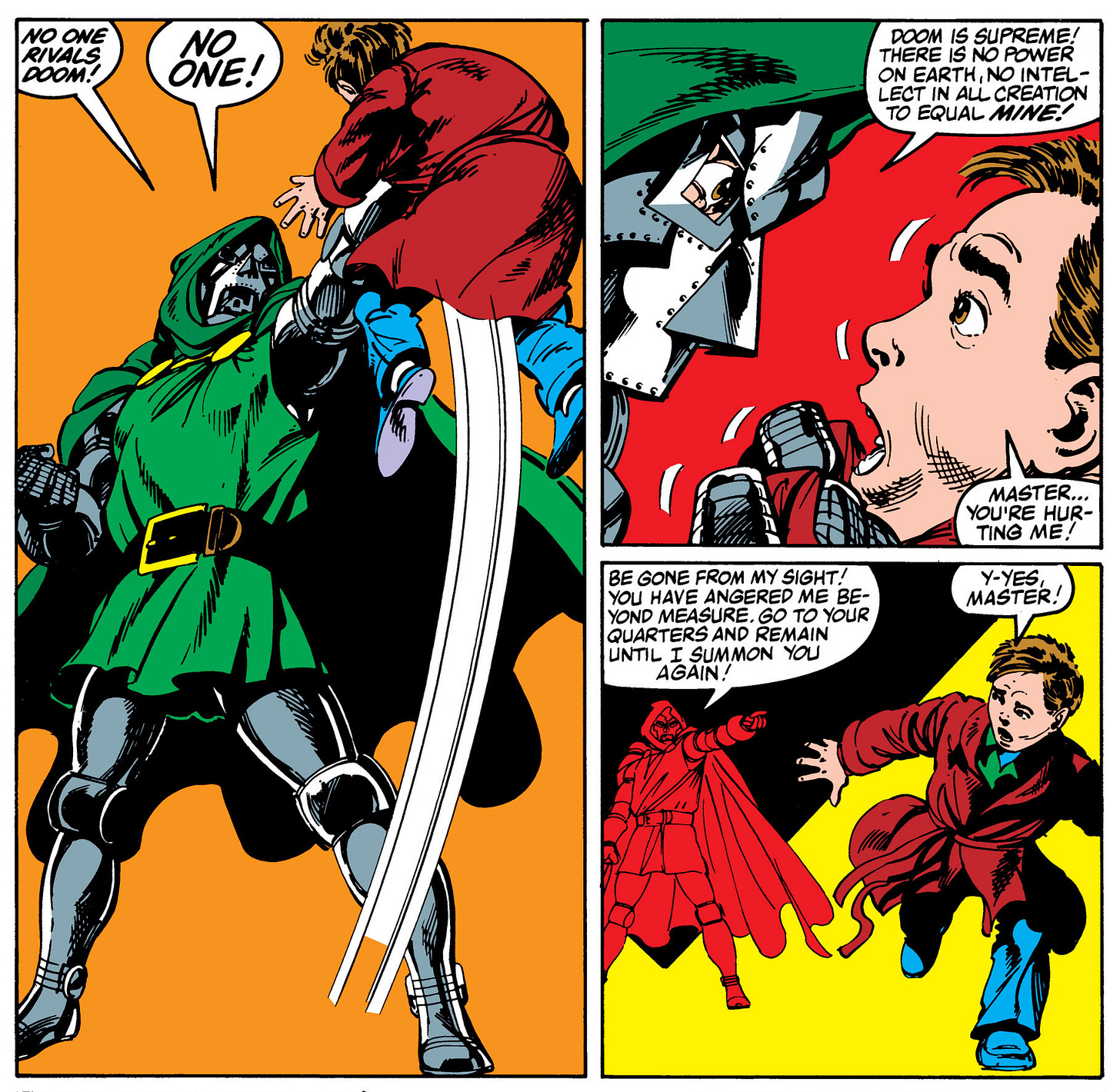

A few pages later, though, we get a pivotal moment with Kristoff, a young Latverian boy whom Doom has taken under his wing. Kristoff’s mother was killed by Doom’s own robots in #248 shortly before Doom retook the country, and feeling responsible, Doom looks after the boy. Devoid of parental instinct, however, all Doom really does is give this poor kid a relentless crash course in The World According to Doom, and at one point, Kristoff makes the mistake of suggesting that maybe Magneto could be on Doom’s level.

Without hesitation, Doom lifts Kristoff overhead, ranting about his inherent supremacy. He sends the terrified boy away, and we never see him again. Doom probably had him killed to take his mind off the uncomfortable truth that if you’re really as powerful as you think, then an innocent child shouldn’t be what prompts you to prove it.

The Kristoff moment takes us back to Byrne’s competing openings of issues #247 and #258. In one, things are not to Doom’s liking, and so he rants and raves. In the other, he has what he wants, and so his wrath subsides momentarily. But that never lasts. Doom may occasionally rest, but he is never at peace. And if he can’t know peace, then no one can. That is the true face of his evil. His allure as a villain is the way in which we can see our own dark reflections within him, unhinged, unapologetic, and unrestrained.

Doom was always a good villain. But he became a great one when Byrne turned him into a sobering reminder that some evils you can’t banish with a sock to the jaw. Some evils persist. They tell us who and what they are, daring us to defy them, secure in the knowledge that there will always be a legion of the craven, clueless, corrupt, and cruel eager to do their bidding. Against such malign intent, all we can do is expel that gloom from our own hearts, and find the courage to persist. After all, despite his brilliance and power, Doom always self-destructs. Nobody knows that better than he does. That’s why he’s so afraid.

Special thanks to everyone who supported Omega Reign’s successful Kickstarter! I’m thrilled to share this epic superhero novel with you. In the meantime, you can still get a late pledge in if you want to secure a copy for yourself or someone you think would like it.